It would be easy to label Widows a heist movie. Or a fierce revenge movie.

Then again, maybe it’s a racially-charged flick about political corruption. Or one heck of a feminist, band-of-sisters film. Or maybe a violent movie about the haves and have-nots.

Truth is, Widows is all of that. And thanks to the fantastic director Steve McQueen, it all meshes together into one perfectly orchestrated symphony of outstanding filmmaking.

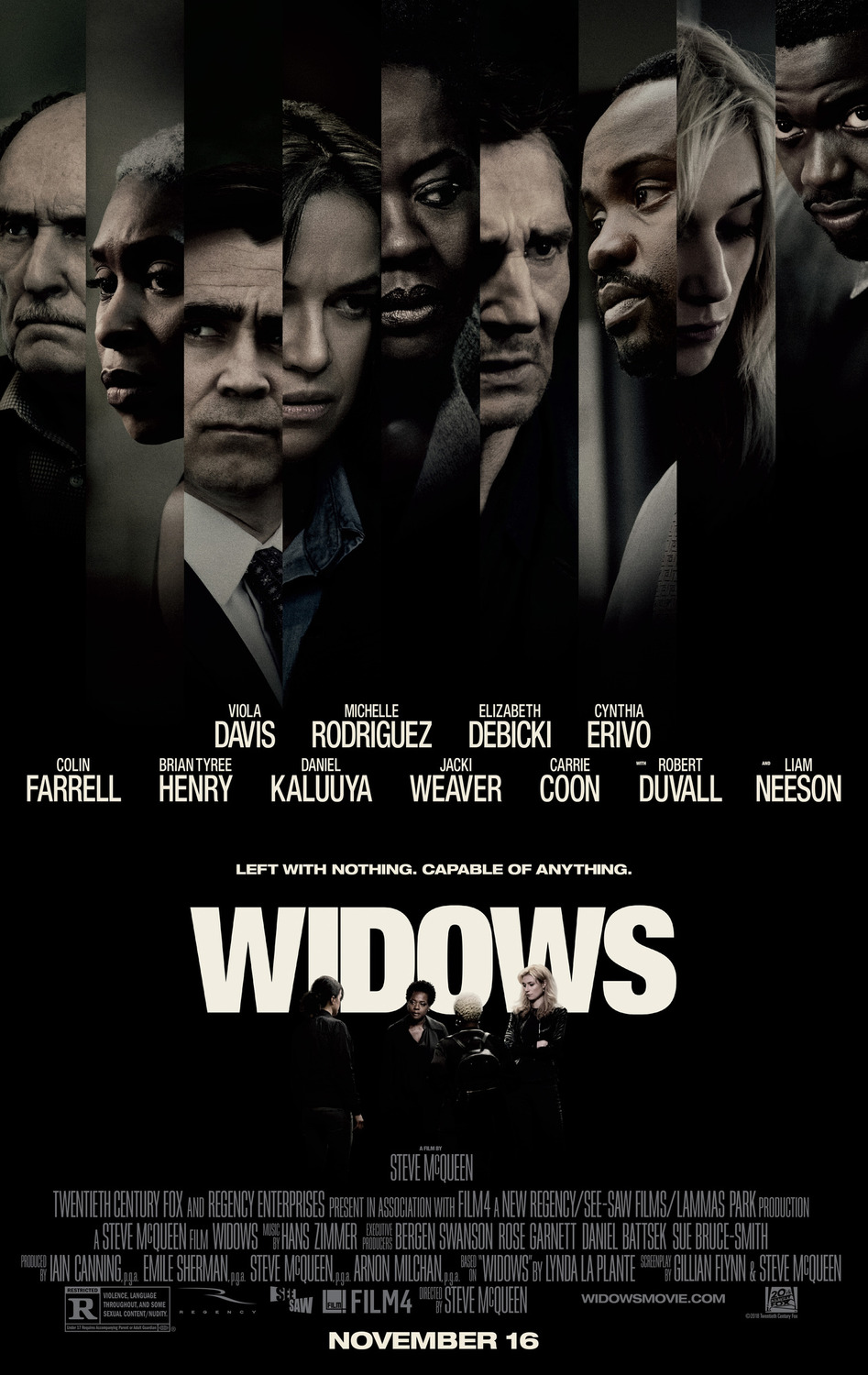

As McQueen proved in 2013 with the Best Picture-winning 12 Years a Slave, he has the seemingly innate ability to take a straightforward story and turn it into something multi-layered and incredibly impactful. In another director’s hands, Widows could have ended up as yet another tired flick about people orchestrating a big ol’ robbery, but McQueen isn’t happy with making ‘yet another’ anything. Working from a delicately crafted script, which he co-wrote with Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn (based on the 1983 British mini-series), McQueen offers a seemingly standard movie that sneaks up on you with its ingenuity and nuance.

Viola Davis leads the way as Veronica Rawlings, a member of the Chicago teacher’s union who is married to Harry (Liam Neeson). In an exquisite opening sequence, we cut back and forth between a quiet, intimate moment of Roni and Harry in bed together and a chaotic, violent car chase that lets us know exactly how everything went so, so wrong; Harry and his crew are killed after a failed robbery, leaving their widows behind.

It turns out Harry stole the money from local kingpin Jamal Manning (Brian Tyree Henry), who is now sending his sadistic henchman (Daniel Kaluuya) to collect. Veronica, not content to simply roll over, discovers Harry’s notebook, which detailed his next planned robbery, and gathers two of the three other widows (Elizabeth Debicki and Michelle Rodriguez) to carry out the plan.

Also at play is Colin Farell as aspiring alderman Jack Mulligan, whose racist father (Robert Duvall) is stepping down as the incumbent. Mulligan is pitted against Manning for the vacant seat.

So, no, this isn’t your grandma’s heist picture.

In fact, there’s very little of Widows that anyone could call conventional. From the storytelling to the shot framing to composer Hans Zimmer’s percussive, discordant score, the film zigs whenever you think it might zag. Cinematographer Sean Bobbitt, who has been behind the camera for all of McQueen’s previous features, captures this entire idea in one single shot halfway through the film. As Mulligan drives off from a campaign stop in a lower-class Chicago neighborhood, we ride alongside, literally—the camera is mounted on the outside of the car for the duration. During the sixty-second ride back to Mulligan’s house, the setting seamlessly slides from skid row to the high life. It’s an innocuous enough idea, but it’s brilliant execution heightens the overall effect.

Widows is already getting a fair share of Oscar buzz, and deservedly so. Everyone is at the top of their game, both in front of and behind the camera. Come for the heist flick, leave with your socks blown off at how well a heist flick can be done.

Rating

5/5 stars