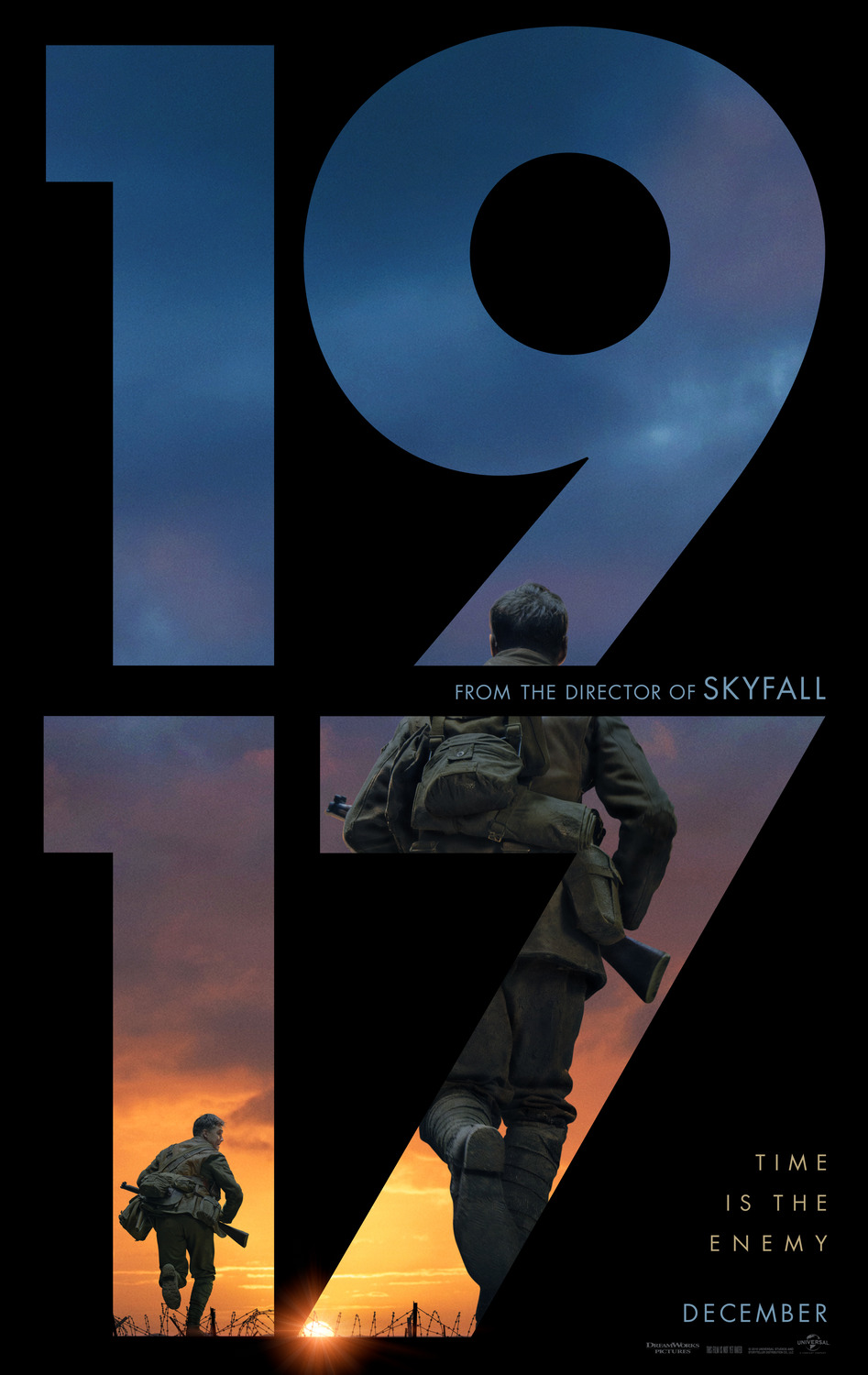

By now, the secret (if it ever qualified as one) is out. Director Sam Mendes’ World War I epic 1917 is made to appear as though it is (for the most part) one, long continuous shot. What could, though, be simply tossed aside as a gimmick included solely to get people talking about the film is instead is one of the key reasons 1917 has emerged as one of the best pictures of the year. From even the first few minutes, it’s clear that Mendes’ vision has a defined purpose, which instantly shreds any notion that the director just, you know, wanted to try something different.

Set on an overcast day in April 1917, the film begins with a pastoral shot of wildflowers blowing gently in a field before pulling back to reveal that we’re behind the British bunker on the Western Front in France. Lance Corporals Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) and Schofield (George MacKay) are called into the dugout of General Erinmore (Colin Firth) and given the unenviable task of delivering a message to a British battalion (including Blake’s older brother) two towns away. The battalion is to call off its planned attack of German forces in the morning; the enemy has set a trap that has doomed the British charge before it even begins.

For the next two hours, the camera rarely slows down and never stops as we follow along through the trenches, across abandoned battlefields, past bombed-out villages, and into the heart of the battle. And because of the extended cuts (reportedly nine minutes on average), the story has time to breathe, and no detail is spared along the way. The ten-minute slog across a muddy, death-strewn No Man’s Land would no doubt have been edited into a brisk, minute-long jaunt in any other movie, but here we get to walk right alongside Blake and Schofield the entire way, experiencing everything they do in real time. Some of it is innocuous (a quick chat about cherry trees), some of it is utterly compelling (a dogfight that leads to a fiery rescue), but every second of it feels as authentic as if it were ripped directly from history books.

Working alongside the great cinematographer Roger Deakins (who should immediately clear space on his mantel for Oscar number two), Mendes has created an immersive and legitimately war-is-hell experience instantly reminiscent of the first half-hour of 1998’s Saving Private Ryan—though not quite as graphic or insanely frenetic. Even Mendes’ decisions about “the little things” pay off, including a reliance solely on natural light throughout and strict attention to period costumes and set decoration. The resulting verisimilitude allows us to experience war at its worst and man at his best, as two soldiers take us (almost literally) on their backs for a hellacious mission and leave us all in awe at what we’ve just witnessed.

Rating

5/5 stars