Retelling (and retooling) one of the world’s most popular stories is a lofty ambition by any measure. Purists and scholars will undoubtedly find fault, avid fans of an earlier version may scoff, and it could be a hard sell to those who have shown no interest before.

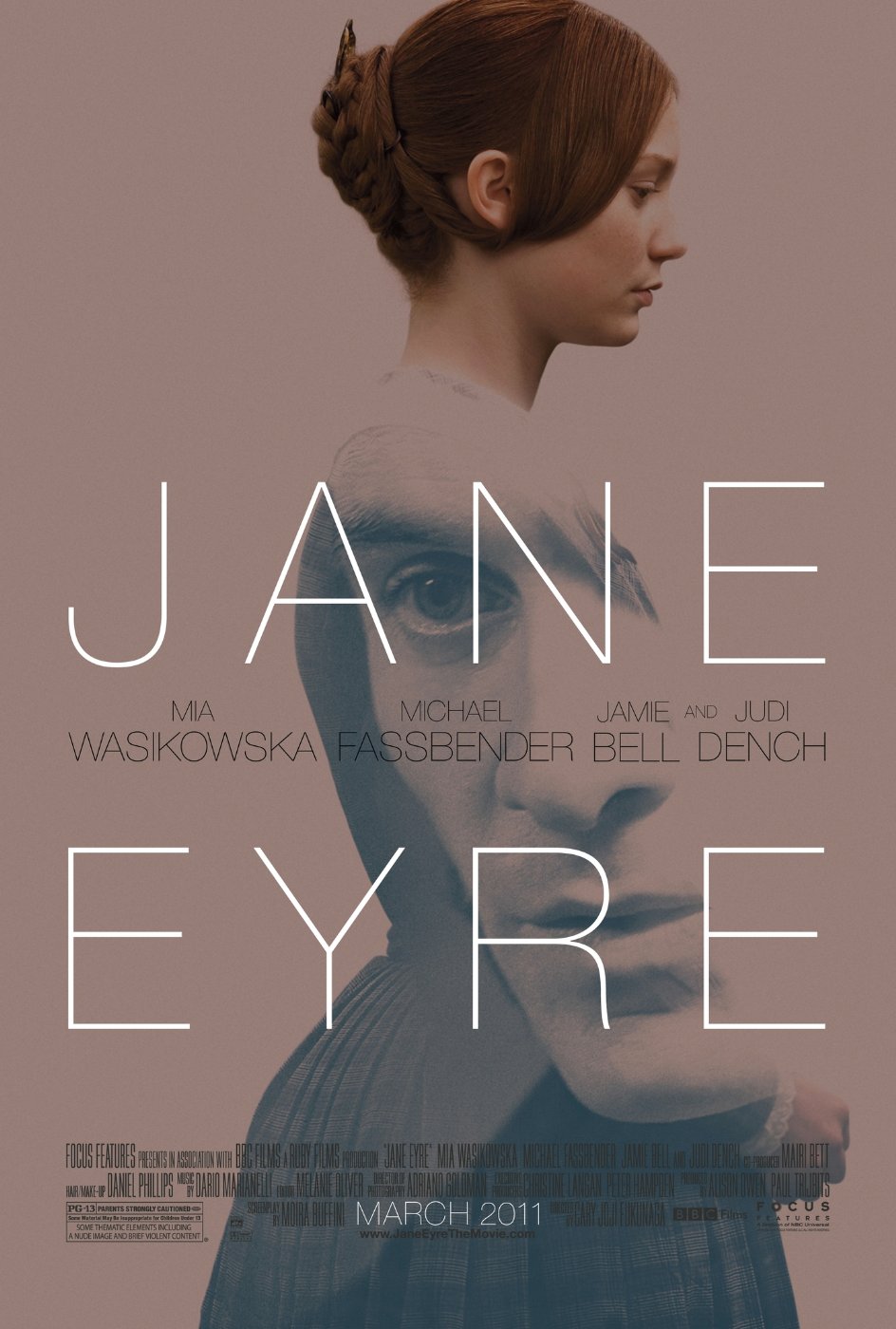

But don’t cry for screenwriter Moira Buffini (Tamara Drewe). Her 2011 version of the Charlotte Brontë classic Jane Eyre is brilliant—a delicate though riveting screenplay, which, in the capable hands of director Cary Fukunaga (Sin Nombre), becomes a motion picture that should captivate even the purists.

Mia Wasikowska (Alice in Wonderland) is Jane, plain as ever, though as independent, honest, and strong, too. The action begins fully two-thirds of the way through the book, with Jane’s flight from Thornfield and her arrival at the home of St. John (Jamie Bell, The Eagle). We then learn about her cruel childhood, both at the hands of her aunt and then again at Lowood School, through brief flashbacks. They’re cursory, sure, but they give enough of a picture that we clearly understand the hardships she faced. (Her later, more tolerable, years at Lowood are all but ignored.)

When she is finally met at Thornfield by Mrs. Fairfax (the always excellent Judi Dench) to serve as Governess to a young French girl named Adele, Jane has matured into a beyond-her-years woman of eighteen– just in time for her to meet Rochester (Michael Fassbender) himself. The two spend many quiet moments conversing in front of the fire, and these dialogues, thought cribbed from the original text, are among the most interesting and entertaining moments of the film.

By the time we reach the famous Jane Eyre secret, we’re already so deeply invested in all these characters that it’s still a shattering moment for those who already know the plot backwards and forwards. The credit here goes primarily to Wasikowska and Fassbender, whose performances are among the best of the year so far, primarily because they are so understated and honest. Buffini, though, is also a key reason for Jane Eyre’s success. She has a true gift for the language of the times, and though she often paraphrases Brontë’s original text, it never sounds fake or forced.

It’s also impossible not to be struck by how quiet and almost ethereal the film is; the score by Oscar winner Dario Marianelli (Atonement) often consists of just a few plaintive notes from a single violin or, at most, a chamber quartet, and many of the lines are spoken in almost a whisper. Adding to the mood is the fact that most of the evening scenes are lit entirely by candlelight. It’s a small touch, but it adds a level of authenticity that pays dividends.

Fukunaga deftly puts all of this together into a movie that instantly transports you directly to the pages of the novel. His incredible attention to detail, combined with the stunning cinematography from his Sin Nombre colleague Adriano Goldman, results in a dark, brooding, almost Gothic film that is as good as you could hope for, Brontë scholar or not.

5/5 stars