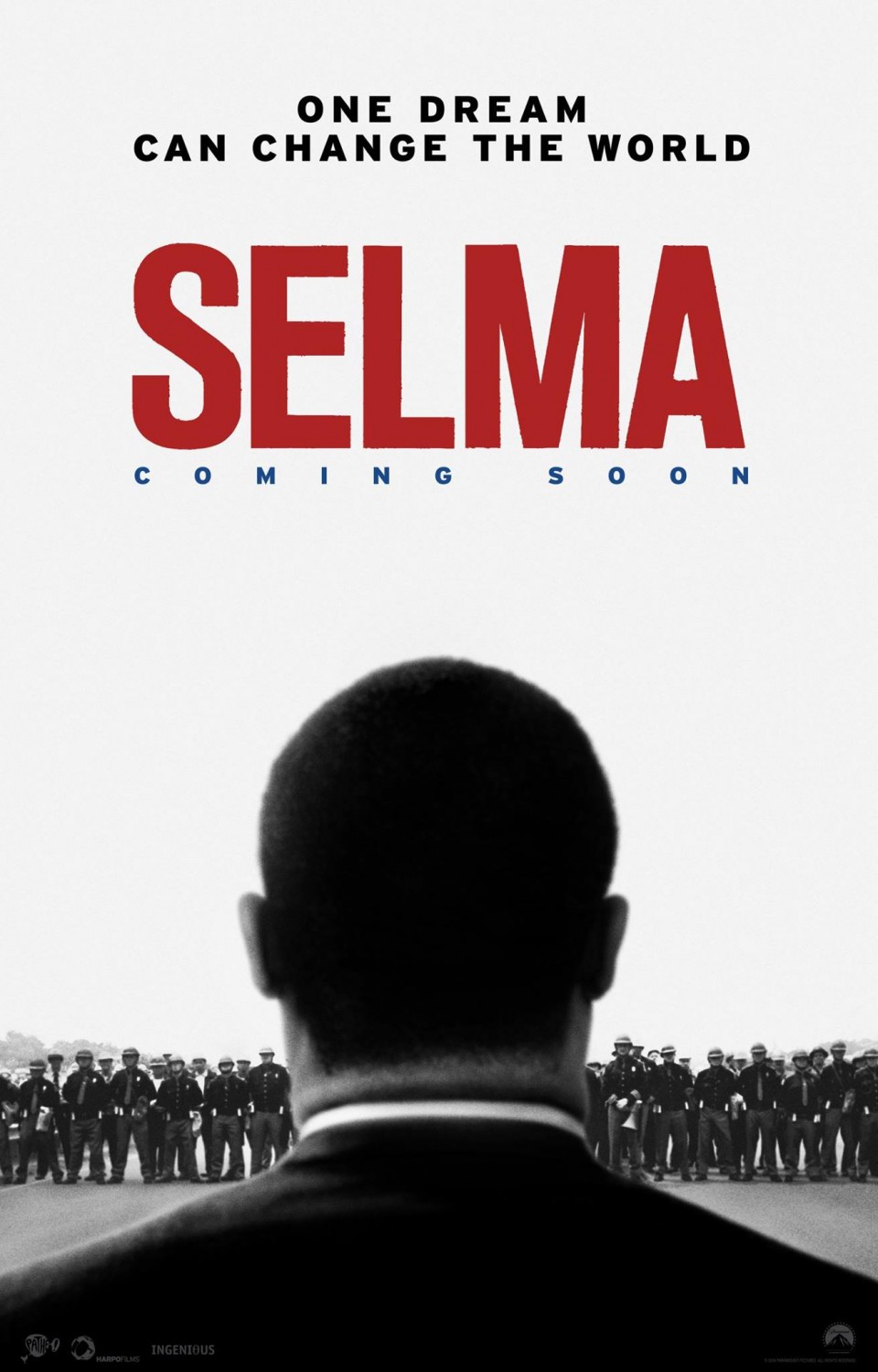

I’m not quite sure how we’ve never, at any point in the 45 years since his death, had a feature film about Martin Luther King Jr. And while Selma isn’t exactly a biopic (instead focusing on just the six months between his winning the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize and then leading the Civil Rights march from Selma to Montgomery), it’s a incredible and indelible portrait of the man and his times.

Had it been released six months ago, Selma would still have packed quite a punch, showing us how far we’ve come but also how far we still have to go in this country. But in the wake of Ferguson and the other racially-charged crimes that have made headlines lately, it’s even more timely. Simply put, Selma should be required viewing for everyone middle school-age and above; it’s that powerful and relevant.

Director Ava DuVernay (Middle of Nowhere) doesn’t pull any punches with her depiction of the terrors that faced blacks in the 60s. In fact, within the first five minutes of Selma, you’ll (almost literally) get blown through the back of the theater. From Jimmy Lee Jackson’s murder to the lynching of Boston minister James Reeb, DuVernay makes sure we have a front row seat to history– not only the tragic, though, but also the triumphant. Aside from a gross misrepresentation of President Lyndon Johnson’s role during those years (more on that in a minute), you’ll emerge from the cinema with a clear and horrifying image of just how difficult but essential King’s struggle was.

David Oyelowo (The Help) captures the essence of King the way Daniel Day Lewis became President Lincoln. Everything that comes out of his mouth, courtesy of novice screenwriter Paul Webb’s nearly flawless script, is a schooling in eloquence and passion– whether it’s a quiet conversation in his home with wife Coretta (Carmen Ejogo) or a fiery speech from the pulpit. The rest of the supporting cast, including Colman Domingo as Ralph Abernathy, Andre Holland as Andrew Young, and Stephan James as John Lewis give head-turning performances that only augment the film’s gut-wrenching power.

As for President Johnson, the fact that DuVernay (or, more accurately, Webb) made him essentially the villain is troubling. To watch Selma is to come away with the idea that LBJ was Dr. King’s adversary, fighting the Civil Rights movement at every turn. History, of course, tells us otherwise– which makes the portrayal for (apparently) the sake of dramatic tension, the film’s lone misstep.

All in all, though, DuVernay has crafted not only one of the best films of the year but also, perhaps, the most important– a poignant mini-portrait of one of the 20th century’s most influential men in his most influential hour.

5/5 stars